WOMEN

Toxic Gender Stereotypes and the Impact of Socialisation

30th November 2020

We witness gender stereotypes every day, but how many of us truly notice? How much of it is so ingrained into our culture and psyche that we are simply blind to it? If you are now asking yourself these questions, then perhaps that proves the point; this is, in fact, the exact purpose of stereotypes. They are a form of unconscious bias which allows us to make sense of the world around us by categorising everything we see – from gender to sexuality and race. They usually serve a useful function by providing us with mental shortcuts to spare us any unnecessary cognitive effort; however, they are often detrimental and limiting when we, or indeed others, do not conform to these straightforward dichotomies. If individuals are not properly informed about gender, sex and stereotypes they can fall into some dangerous traps in the course of their lives and may suffer discrimination, sexual violence or harassment, poor mental and physical health and poor academic or career prospects.

Firstly, what exactly is gender and how is it different to sex? What are gender stereotypes? Sex is biological and refers to an individual’s physical characteristics such as the genitalia and chromosomes they were born with; it does not determine a person’s gender identity. Gender, on the other hand, is a personal, private feeling of one’s own identity and is socially constructed based on self-perception, expression and behaviour. The difference between the two is key to understanding the issue of gender stereotypes and the resulting gender-based discrimination. Gender stereotyping is an overgeneralisation of the differences between certain groups based on their characteristics or attributes, and they serve to reinforce the idea that each gender and the behaviours associated with it are binary.

This is too simplistic and not reflective of reality; gender identity and sexuality exist on a spectrum, and stereotypes create a disconnect in the minds of those observing the behaviour of a particular individual when, in an attempt to ascertain their gender, they perceive the behaviour as not in line with what they expect. This can lead to discrimination and unfair treatment across various aspects of an individual’s life – in the workplace, the military or when accessing healthcare, for example. Gender stereotypes can also influence a young person’s classroom experience and subject choice; in an Institute for Physics study, only 7% of engineering apprenticeships (a stereotypically male career) in the UK were filled by girls, whilst only 10% of primary school teachers (stereotypically female) in Scotland were men.

“Gender stereotyping is an overgeneralisation of the differences between certain groups based on their characteristics or attributes, and they serve to reinforce the idea that each gender and the behaviours associated with it are binary”

Although much of the discussion surrounding gender-based discrimination is focused on women, men also suffer the consequences of unconscious bias. As the author, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie explains “by far the worst thing we do to males – by making them feel they have to be hard – is that we leave them with very fragile egos” – this quite poignantly outlines the damage ‘toxic masculinity’ can inflict. Toxic masculinity describes a set of behaviours and beliefs that can include: the suppression of emotions, the masking of distress and maintaining an appearance of hardness or stoicism. Men or boys openly expressing emotion is often viewed as a weakness or something inherently ‘feminine’. According to the American Psychological Association (APA), these beliefs have been linked to significant negative outcomes for men and boys such as aggression and violence, a disproportionately higher risk for school discipline, academic challenges, and a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and substance abuse. Although power, privilege and sexism often confer certain benefits to men, it can also force them into a narrow set of roles, thereby also trapping them. APA statistics confirm this effect; while men dominate society professionally and politically, they are 3.5 times more likely to die by suicide than women (despite reporting less depression), while their life expectancy is 4.9 years shorter.

Men who are socialised to show stoicism, dominance and aggression are also less likely to engage in healthy behaviours and show a certain reluctance towards self-care; they tend to normalise risky behaviours such as heavy drinking and using tobacco, thereby putting themselves more at risk of the consequences of such risk-taking. This can be linked to the way men are brought up – to be sufficient, independent and not express any vulnerability. The need for men to maintain a brave face and be the ‘provider’ for his family can also interact with other forms of discrimination, forming an even more toxic combination. Racial discrimination among Black men is associated with hypertension and depression – a direct result of enduring prolonged stress. Black males are also at risk of harsher punishments than those of different groups, as they are often viewed with suspicion by schools and law enforcement, as Black Lives Matter protestors will attest.

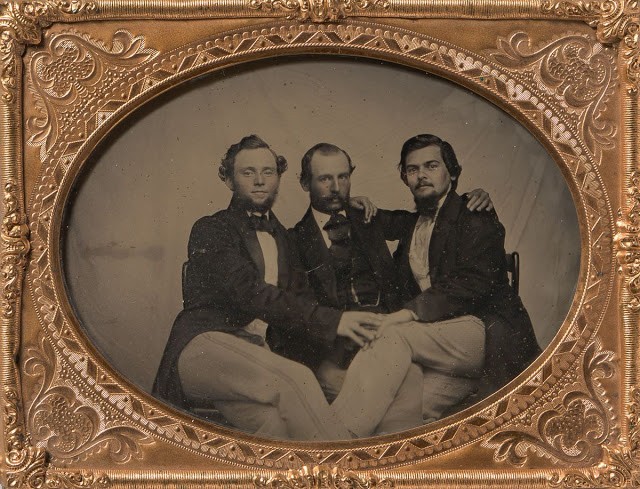

A Photo History of Male Affection (Art of Manliness, 2020)

The perception of gender as something inflexible is particularly detrimental to the wellbeing of transgender individuals. Whilst today there is increased awareness of the diversity of gender identity, there is still much work to be done. Men and boys who identify as gay, bisexual or transgender suffer higher levels of hostility and pressure to conform to gender norms. This can be extended to the military – in 1994 President Clinton introduced the ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ policy which permitted gay men, bisexuals and lesbians to serve their country, provided they remain in the closet. Whilst this was overturned by the Obama administration, President Trump not only reversed this but went one step further by instituting a complete ban on transgender individuals serving in the military, citing a rule whereby the US government pays their medical costs. Trump is quoted as saying “our military must be focused on decisive and overwhelming … victory and cannot be burdened with the tremendous medical costs and disruption that transgender in the military would entail.” Transgender individuals face economic and social marginalisation as a result of this kind of discrimination – many have been fired, lost their homes or are unable to access the healthcare they need.

In their article ‘Bosom Buddies: A Photo History of Male Affection’, Brett and Kate McKay outline the painful shift in gender stereotypes and norms that has taken place over the last century which has led to the decline of the expression of affection between close male friends. Society has now sexualised simple gestures of companionship such as holding hands and hugging, with many men reluctant to engage in these behaviours for fear of being labelled ‘gay’. Before the 20th century, same-sex sexuality was thought of simply as something you did, not something you were. However, this attitude soon shifted from being a practise to a lifestyle and finally, an identity. Many psychiatrists and ministers viewed it as a mental illness and something to be strongly discouraged. Thus, it became stigmatised. The McKay article reveals a beautiful photographic display of affection between men, the likes of which we no longer witness in our modern, hyper-sexualised society. One of the reasons these male friendships were so intense was because socialisation was highly segregated by sex, therefore men spent most of their time with other men, likewise with women.

A Photo History of Male Affection (Art of Manliness, 2020)

Gender norms also affect women in various detrimental ways. The ‘purity culture’ is just one example. This occurs when a woman is taught that her value lies solely in her sexual purity and virginity. This has very real consequences, as Elizabeth Smart can attest. After being kidnapped, repeatedly raped and incarcerated, Smart, who had a religious upbringing, says she began to understand why others wouldn’t even try to escape, as she felt worthless. She believed that she had nothing to offer society if she was ‘sexually impure’. Our society perpetuates many double standards – men often get a free pass for their sexual behaviour, while women are judged and earn a negative reputation. Women who display any sexual agency or carry condoms in their purse are branded ‘sluts’. This occurs despite the fact that women are socialised to ‘control the brakes’ of sexual responsibility; there is little mention of the male agency.

The fashion industry, although mainly targeted at women, has its foundations in the gratification of the male gaze. Strict school dress codes and rules governing the appropriate length of a woman’s skirt combine to reinforce the patriarchal control over a woman’s body. The strict grooming and fashion guidelines enforced by airlines for their female cabin crew contribute to the idea of air stewardesses being a part of the service the airline provides for its customers, a way of keeping the ‘mile-high club’ fantasy alive by putting women on display for consumption. The use of clothing to discriminate against and control women is also prevalent in legal circles too – how many times have we witnessed an item of women’s clothing being used as evidence by the defence in a rape/sexual assault trial? When used in this way, clothing and the fashion industry becomes a means of victim-blaming. Also worth noting is the controversy in France over the banning of the burkini and the continued politicisation of women’s bodies in the public sphere.

An interesting perspective on gender norms and stereotypes is the Irish nationalists’ use of women as a means of establishing a sense of identity, of nationhood and ‘Irishness’. Arthur Griffith once said ‘all of us know that Irish women are the most virtuous in the world’. A woman’s virtue was henceforth inextricably tied up with the concept of nationhood, burdening women with the task of being guardians and upholders of virtue in the home. In an attempt to differentiate and distinguish an ‘Irish identity’ from their ‘morally corrupt’ former British colonisers, it has been argued that church and state collaborated to impose a strict set of Catholic social mores and values which subjected women to intense scrutiny of their sexuality and social behaviour. Unmarried mothers were stigmatised for ‘bringing shame’ on the family and many of them were incarcerated in Magdalene Laundries where they suffered horrific physical, verbal and emotional abuse at the hands of the nuns and clergy, even if their pregnancies were the result of rape. Such women were exploited and treated like slaves while their babies were forcefully (and illegally) adopted. There did not exist any male equivalent of a Magdalene Laundry for the fathers of so-called illegitimate children; in fact, until 1998, adoption law in Ireland did not even address the issue of unmarried fathers’ consent at all – they were either absolved of all parental responsibility or they were not regarded as parents at all.

“Arthur Griffith once said ‘all of us know that Irish women are the most virtuous in the world’. A woman’s virtue was henceforth inextricably tied up with the concept of nationhood, burdening women with the task of being guardians and upholders of virtue in the home”

Whilst the #MeToo movement has done much to raise awareness of gender-based discrimination, sexual violence and gender pay-gap, society still has a long way to go. There is a huge issue with sexual assault prevention programmes/strategies – they are simply too little, too late. They often take the form of educational classes on college campuses or workplace seminars; however, according to the CDC, 43.2% of women who have been raped or suffered rape attempts were actually attacked before they were aged 18. This suggests we need to take action much sooner. One significant risk factor for a person becoming a sexual predator is the belief in and adherence to conventional gender stereotypes. This can be offset by starting the education process early – gender stereotyping begins very early on in life, with many parents-to-be hosting gender reveal parties, dressing their new-born baby girls in pink and infant boys being bombarded with toy trucks. During the teen years, male gender stereotypes start to incorporate ideas of dominance and aggression, while female norms centre around sexuality and attractiveness. By encouraging toddlers and young children to engage in cross-gender interactions such as play-dates, attending mixed-sex schools and participating in mixed-gender sports, we can help to reduce these stereotypes and prevent children from internalising rigid and unrealistic gender norms which may limit their opportunities and quality of life.

Featured photo by Freepik