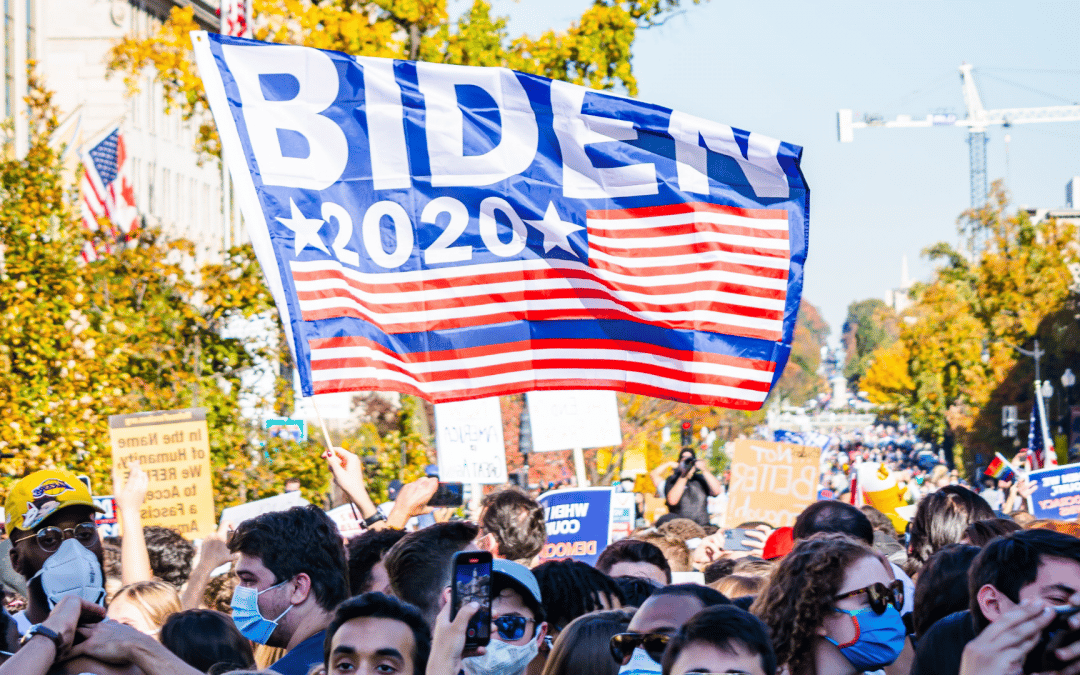

Adam O’Neill Mayós on why libertarian Javier Milei’s success amongst Argentines in Ireland and beyond has turned Argentina into a macroeconomic experiment.

Ideas Collective Participant Implements Public Health Awareness Programme

‘’In an unequal world, our response to COVID-19 cannot be one size-fits-all’’ –Médecins Sans Frontieres

For public health interventions to be effective, they must be locally curated, and responsive to the realities of inequality. Even on a national scale, the Covid-19 pandemic has not been experienced by any one population homogeneously. How could we therefore think the solution to be any different?

There is no easy answer to a public health crisis, especially in global terms. It would be a mistake to assume that the challenges faced by any given geographical region are faced by all. Rather, the public health determinants and barriers withholding the responses to the pandemic have demonstrated great geographical, cultural and political variance.

Community Wellness Africa is an NGO based in Nairobi, Kenya and is currently running community initiatives in the Southwest County of Kisii. Robert Ogugu, the founder of the organisation participated in STAND’s Ideas Collective where he progressed to secure funding for his organisation in order to implement a Covid awareness raising project in Kisii County. The Ideas Collective is an annual social incubator programme for students and graduates such as Robert. Thanks to his success in the Ideas Collective, and with the help of his team, Evelyn, Dave, Denzil, Trizah and Makepeace Njeri, Community Wellness Africa was able to initiate their latest project tackling community awareness and health education addressing Covid prevention.

Denzil Okari of Community Wellness Africa, Mr. Thomas Omwenge, Director at St. Thomas Academy, and Mr. David Nchaga, Head teacher at St. Thomas Academy. Location is St. Thomas Academy in Kisii County, Kenya.

The organisation strives to promote the wellbeing of vulnerable communities in Southwest Kenya by adopting a public health approach in the implementation of their various grassroot projects. The focus of their Covid-19 awareness project is centred around preventive rather than curative responses to the pandemic. The project takes on a multi-level approach focused on community awareness campaigns as well as vaccination roll out. Robert and his team work in correspondence to what they believe are the pillars to sustainable public health development; healthcare, education and economic empowerment.

By working in line with these interdependent pillars, Community Wellness Africa aims to provide an efficient and effective impact on the lives of the communities they work for and thus limit the danger of Covid-19 within the villages. By focusing on health education and community sensitization, Robert and his team are not only working to limit the impact of the virus, but also to lessen the dependency on unguaranteed overseas aid as the only way of surviving the pandemic.

In some rural parts of Kenya, access to the internet and communication services are minimal, and at that, extremely expensive. Community Wellness Africa focuses on overcoming barriers to accessing information and public health provision by adopting a specific cultural response. As many African countries face an array of financial, political and logistical barriers in accessing curative solutions to the pandemic, sufficiency in the supply of vaccines as well as the infrastructure needed to roll them out is a great challenge.

Even with the help of donations from Europe and North America, the number of vaccines being sent to Kenya is simply not enough. “There are doubts whether these are genuine donations because sometimes the vaccines sent to Africa have a short expiry date, some expire while on transit to their intended destinations,” Robert explained.

Nevertheless, the main challenge is the quality chain in place once these expiring vaccines arrive. “If help comes, I think it should come as a package, it should be complete with logistical considerations in place and vaccines should have long shelf-life dates. And at that, there should be adequate public awareness raising initiatives for faster vaccine uptake.”

Denzil Okari of Community Wellness Africa giving a health talk during the implementation of the program. Location is Tracer Academy in Kisii County, Kenya

Prevention in terms of public health education is at the essence of the project in Kisii county. One of the most unique elements of the organisation however, is the curated approach they have taken in order for information to be accessed by the maximum number of people in the most equitable manner possible.

Regarding using the radio as a primary means of disseminating information, Robert explained how radio and other social media channels have played both positive and negative roles in spreading information about the pandemic, especially in the Global South. Like most media, communicating through outlets such as the FM channels in Kenya is bound within a web of complicated power structures, political ties, and misinformation. “Radio and television sets are not accessible to all the people living in rural areas” said Robert. He further explained how in traditional communities such as those working with Community Wellness Africa “The father of the house is the owner of the radio and would prefer tuning it to channels that discuss local politics or play bongo music.”

By targeting schools as the entry points to these rural communities, Robert Ogugu’s team is able to incorporate pupils, students, teachers, and other staff working in the education and health sector by encouraging them to take active roles as agents of health promotion. Linking in with the Covid-19 Facemask program, public health information and resources from the organisation’s workshops reach households more effectively, and therefore the wider population. “We definitely cannot supply the entire community with facemasks, but the few which we give out pass a certain message in that locality, that everyone should wear a facemask, and this is creating an overall positive impact. For example, those who participate in the programme and those who receive a facemask become agents of information and can share what they learned with their friends and family, thus leading to behavioural change in the community. This can be evidenced by by people adopting the wearing of facemasks when in public places, embracing handwashing hygiene, practicing social distancing, and getting vaccinated’’ explained Robert.

Public health education and community awareness projects such as that being run by Community Wellness Africa are breaking the boundaries of inequity and inefficiency which continue to disable the success of other approaches to the Covid-19 pandemic. Good health and well-being are more than the absence of a disease. As expectations of services needed to provide curative solutions to viral diseases, such as Covid-19, continue to increase, locally curated and community focused responses are needed.

Community Wellness Africa is currently fundraising to provide the communities in Kisii County with the services they need to respond to the pandemic. The team plans to install handwashing facilities in three of the schools under this program at a Cost of Euro 5,000 per school.

If you would like to donate or partner in this project, please visit— www.communitywellnessafrica.org or write to [email protected]

Featured image is of Denzil Okari of Community Wellness Africa and Madam Marion, a teacher at Tracer Academy. Location is Tracer Academy in Kisii Country, Kenya.

All photos by Robert Ogugu.

This article was supported by: STAND News and Communications Intern Elaine and Engagement Coordinator Aislin

New From STAND News

What are the economic impacts of Javier Milei’s presidency?

Missiles over Mouths: Could government policy in North Korea be leading towards a second famine?

Forestalling a second famine in North Korea is contingent on the actions of the governing regime. Despite this, leader Kim Jong-Un prioritizes organizing a National Holiday to celebrate his missile might, before tackling the “serious political issue” of food scarcity.

Change, community, and compassion: The STAND Changemakers Academy Showcase

On Friday 22nd March, members of the STAND community gathered at Richmond Barracks to celebrate the end of the first Changemakers Academy.

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTER

Stories straight to your inbox that challenge how you think about the world.